\

---- Burgundian | ----East | | East --------- Gothic --------West | | | | | ----Gepid | ---- Lombardic | | | ---- Vandalic | | ----English | |(Old, Middle, New) | | | | ----East | ----Ingvaeonic----- | | ---- Frisian -----------West | | |(Old, Middle, New) | | | ----North West - | | | | ---Low Saxon---Middle Low German---- New Low German | | ----Low German---------- Dutch-Flemish | | (Old, Middle, New) ||----Low Franconian----Middle Dutch---- Afrikaans | | ----Alemannic | | | | | ----Bavarian | ----High German---- | (Old, Middle, New) ----Franconian | | | ---- Yiddish | | ----Danish | | (Old, New) | | | ----East--------Swedish | | | (Old, New) | | | | | ---- Gutnish North -- | ---- Faroese | | | ---- Icelandic ---- West --------- ---- Norwegian --------Nynorsk | --------Bokmal ---- Nornrelationship between East and North Germanic and the principle branches of West Germanic leads many scholars to divide all Germanic into five equal-weight branches (clockwise from the north): North, East, Elbe, Rhine-Weser, and North Sea Germanic. Elbe Germanic corresponds roughly with High German; Rhine-Weser with Low Germanic; and North Sea with Anglo-Frisian Germanic. Wanderings of the Germanic tribes, especially during the Völkerwanderung period (400-700 CE), permitted much mixing of the dialects. About 80% of Germanic roots are non-Indo-European.

The East Germanic subgroup is represented mainly by the Gothic language which has been preserved in written records of the 4th-6th cc. It was the language of the first Teutons (namely the Goths) who, in the second through fourth centuries, left the coast of the Baltic Sea and started out on their migrations to the south-east (first to the Danube and Black Sea areas from the Germanic homeland). The languages of these people, which are poorly attested except for West Gothic, show characteristic differences from West and North Germanic branches. The East Germanic Languages were Gothic, Vandalic, Burgundian, Lombardic, Rugian, Herulian, Bastarnae, and Scirian. The East Germanic languages were marginalized from the end of the Migration period. The Burgundians, Goths and Vandals became linguistically assimilated to their respective neighbors by about the 7th century, with only Crimean Gothic lingering on until the 18th century.

Gothic was the East Germanic language of the Germanic speaking people who migrated from southern Scania (southern Sweden) to the Ukraine. From there the West and East Goths migrated to southern Gaul, Iberia, and Italy in the fifth and sixth centuries C. E. The Gepids were overcome by the Lombards and Avars in the fifth century and disappeared. Gothic is recorded in translations of parts of the bible into West Gothic in the fourth century C. E. and by names. The Gothic Bible of AD 350 is the earliest extensive Germanic text. Gothic is extinct. The last Gothic speakers reported were in the Crimea in the sixteenth century C. E.

Lombardic was the East Germanic language of the Germanic speaking people who invaded and settled in Italy in the sixth century C. E. It is said that Lombardic participated in the so-called second sound shift which is primarily attested in High German.

Burgundian was the East Germanic language of the Germanic speaking people who ultimately settled in southeastern Gaul (Southeastern France, Western Switzerland, and Northwestern Italy) in the fifth century C.E. It is extinct.

It is said that the East Germanic languages were probably all very similar. All of the East Germanic languages are extinct.

The North Germanic subgroup of languages is preserved in runic inscriptions dated from the 3rd to the 9th cc. which were made in an original Germanic alphabet known as the runes or the runic alphabet. These were the languages of the Teutons who stayed in Scandinavia after the Goths had gone. Their language known as Old Norse, or Old Scandinavian, was later divided into Old Danish, Old Norwegian and Old Swedish. The process was connected with the political division and constant fights for dominance. The earliest written records in these languages date from the 13th century.

Besides, the NG group includes Icelandic and Faroese languages the origin of which goes back to the Viking Age.

West Norse is the western branch of the North Germanic languages used in Iceland, Ireland, Norway, the Hebrides, Orkney, Shetland, and the Faroe Islands. It diverged from common North Germanic about 800 C. E. Its living descendents are Norwegian, Icelandic, and Faroese. Terminology for varieties of West Norse is vexed. Old Icelandic and Old Norwegian are sometimes called Old West Norse, with Danish and Swedish being Old East Norse. Other sources refer to Old Icelandic as Old Norse.

East Norse is the eastern branch of the North Germanic languages used in Denmark and Sweden and their present and former colonies. It diverged from common North Germanic about 800 C. E. Its descendents were Danish, Swedish, and Gutnish.

Faroese is a contemporary Western North Germanic language spoken in the Faroe Islands. It is a descendant of West Norse; the number of speakers (1988) is 41,000.

Gutnish is a contemporary Eastern North Germanic language spoken on the island of Gotland. It is first attested in legal documents of the fourteenth century C. E. Some authorities consider Gutnish to be merely a dialect of Swedish.

Icelandic is the contemporary language of Iceland. It is a very conservative descendent of West Norse. Frequently Old Icelandic (c. 800 BCE - 1500 CE) is referred to as Old Norse. It is the language of the Norse sagas and eddas. It is said that many Icelandic readers are able to read this literature without much difficulty. The number of speakers (1988) is 250,000.

Norwegian, a contemporary Western North Germanic language, is the official language of Norway. It is a collection of related dialects of West Norse. It has two major written dialects: Nynorsk and Bokmal. Nynorsk is the contemporary descendent of Old Norwegian. Bokmal, also called Dano-Norwegian or Riksmal, is really a form of Danish. Since 1951 there has been a concerted effort to effect a merger of the two dialects. Number of speakers (1988) is about 5 million.

The West Germanic subgroup included several dialects of the tribes which inhabited the territories between the Odre and the Elbe and bordered on the Slavonian tribes in the East and the Celtic tribes in the south: Franconian, Anglian, Frisian, Jutish, Saxon and High German. The Franconian dialects in Middle Ages developed into Dutch and Flemish which are now spoken in the Netherlands and Belgium. Dutch or Flemish is the contemporary descendent of Middle Dutch. With slight differences, the same language is called Dutch in the Netherlands and Flemish in Belgium. It is one of the two official languages of the Netherlands and one of the three official languages of Belgium; the number of speakers (2000) is 20 million.

The whole West Germanic language area, from the North Sea far into Central Europe, is really a continuum of local dialects differing little from one village to the next. Only after one has travelled some distance are the dialects mutually incomprehensible. At times there are places where this does not occur, generally at national borders or around colonies of speakers of other languages such as West Slavic islands in eastern Germany. Normally the local national language is understood everywhere within a nation. The fact of this continuum makes the tracing of the lines of historical development of national languages difficult, if not impossible.

The Dutch language was brought to South Africa about 300 years ago and developed into a separate language, Afrikaans. Afrikaans is a contemporary West Germanic language developed from seventeenth century Dutch. It is one of the eleven official languages of the Republic of South Africa; Number of speakers (1988): 10 million.

The High German dialects gave rise to the literary German language. Yiddish grew from Middle High German dialects adopted by numerous Jewish communities in Germany in the 11th-12th cc. Yiddish existed in two main dialects, West Yiddish and East Yiddish. It developed in Germany in approximately 1050 CE and spread eastward into Poland and Russia. It contains an admixture of German, Romance, Hebrew-

Aramaic, and Slavic. West Yiddish is said to be extinct.

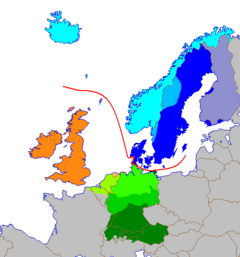

| Picture 3. The Germanic languages in Europe(Source: https://www.answers.com) Dutch (Low Franconian, West Germanic) Low German (West Germanic) Central German (High German, West Germanic) Upper German (High German, West Germanic) Anglic (Anglo-Frisian, West Germanic) Frisian (Anglo-Frisian, West Germanic) East Scandinavian West Scandinavian Line dividing the North and West Germanic languages. |

Eastern Yiddish is spoken in Israel, the United States, Latin America, and Russia. Number of speakers (2000) is about 20 million.

Frankish is the extinct West Germanic language formerly spoken in Northern Gaul and the Low Countries. It was largely swamped by the Latin-derived French. However Low Franconian, an approximate ancestor of Dutch-Flemish, was closely related to Frankish.

Frisian has survived as a local dialect in the Netherlands and Old Saxon as one of the Low German dialects. Frisian is a contemporary West Germanic language spoken in the Netherlands and Germany. It is one of the two official languages of the Netherlands. Of all Germanic languages, Frisian is most closely related to English. Frisian from the earliest records of about 1300 until about 1575 is called Old Frisian. Subsequently Frisian is known as New Frisian. Some Frisian scholars also identify a Middle Frisian period from about 1600 to about 1800. Frisian exists in three major divisions, each of which is subdivided into dialects. The two dialects of East Frisian have been largely replaced by dialects of New Low German which are called East Frisian. North Frisian is divided into about ten dialects. Nearly all modern Frisian literature is in West Frisian which has about six dialects.

In the 5th c. a group of West Germanic tribes started out on their invasion of the British Isles. Their dialects developed later into the English language. Old English (or Anglo-Saxon) is the oldest recorded form of English. It is said to be the language of the three tribes (Angles, Saxons, and Jutes) of West Germanic speaking people who invaded and occupied Britain in the fifth century C. E. It is very closely related to Old Frisian. Old English developed four major dialects: Northumbrian, Mercian, West Saxon, and Kentish. The majority of recorded Old English is in the West Saxon dialect. Old English is characterized by phonetic spelling, a moderate number of inflections (two numbers, three genders, four cases, remnants of dual number and instrumental case), a syntax somewhat dependent on word order, and a simple two tense, three mood, four person (three singular, one plural) verb system. Old English is recorded from the late seventh century onwards. By about 1100 C. E. enough changes had accumulated so that the language is designated Middle English.

Middle English was the descendent of Old English. English after about 1100 C. E. had changed enough to warrant a different designation. Middle English had about five major dialects, Northern, West Midlands, East Midlands, Southwestern, and Kentish. Middle English is characterized by the reduction and loss of inflectional endings and the introduction of a large number of words derived first from Latin through Norman or Middle French and subsequently from Middle Dutch. By the late fifteenth century, East Midlands Middle English, the language of London, had acquired enough changes to be designated Early New English.

2. All the Germanic languages of the past and present have common linguistic features which were acquired during the perio of the Proto-Germanic parent language. We shall consider the common features in phonetics, grammar and vocabulary. One of the most distinguishing features of the group is word stress falling on the first root syllable. In ancient Indo-European, prior to the separation of the Germanic group the position of the stress was free and movable, e.g.

`дом - до`машний - домо`вой – домо`витый;

`свет – све`тить - `засветло - `светлый.

In Proto-Germanic the stress became fixed. Suffixes and endings were usually unstressed. The stress could no longer move in either word-building or in form-building, e.g.

`love - `loving - `lover - `beloved;

`man - `mannish - `manly - `manlike - `manliness.

Throughout the history vowels underwent different kinds of alterations: qualitative (when the quality of the sound is altered, e.g. [o>a] [p>f]), quantitative (when the length is changed), dependent (a sound changes in a certain position or a syllable) and independent (a sound is effected in all positions).

The most important vowel changes in Proto-Germanic were Independent Vowel changes (qualitative changes of [o] and [a] into [a:] and [o:] accordingly) and Mutation of Vowels the essence of which is that allophones of vowels [e] and [u] later developed into separate phonemes: [i, e] and [u, o], accordingly).

The most important feature of the system of the Germanic vowels is called Ablaut, or gradation, which is a spontaneous, positionally independent alteration of vowels inherited by the Germanic languages from the Common Indo-European period. There were two types of Ablaut: qualitative and quantitative. The qualitative Ablaut is the alteration of different vowels, mainly the vowels [e] / [a] or [e] / [o], e.g.

Old Icelandic b e ra (to give birth) – b a rn (baby);

Old High German st e lan (to steal) – st a l (stole).

Quantitative Ablaut consisted in the change of length of the vowel which can be exemplified by the forms of the Greek word “pater” (father):

pat ē r [e:] (nominative case, lengthened stage) – pat ĕ r [e] (vocative case, normal stage) – patros [-] (genitive case, reduced stage).

Ablaut as a kind of an internal flexion functioned in Old Germanic languages in form- and word-building, and most systematically it was used in the conjugation of strong verbs.

As a result of these changes, there came one of the characteristics of Germanic languages, that of the strict differentiation of long and short vowels: [i – i:], [e – e:]. [a – a:], [o – o:], [u – u:].

Another phenomenon common for all Germanic languages was the tendency of phonetic assimilation of the root vowel to the vowel of ending, the so-called Umlaut, or mutation. There were several types of mutation, the most important of which was palatal mutation, when under the influence of sounds [i] or [j] in the suffix or ending the root vowels became more front and more closed.

Goth harjis OE here (army)

Goth domjan OE deman (deem)

Goth kuni OE cynn (kin)

After the changes in Late Proto-Germanic the vowel system contained the following sounds: [i]–[i:], [e]–[e:], [a]–[a:], [o]–[o:], [u]–[u:].

Speaking about the Germanic consonants, it is necessary to mention two prominent shifts known as Grimm’s Law and Verner’s Law. The First Consonant Shift, or Grimm’s Law, was discovered by the German linguist Jacob Grimm in 1822 (Jakob Grimm (1785-1863) was the brother of Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859). The Grimm brothers are best known as the collectors of "Grimm's Fairy Tales."). Grimm's Law describes the phonetic shift of initial stops from their Indo-European values to their Germanic values: voiceless stops become fricatives, voiced stops are devoiced, and voiced aspirate stops become deaspirate. According to the law, there were three acts of consonant changes which gradually lead to the development of the modern system of vowels. The changes were as following: 1) voiceless plosives developed in Proto-Germanic into voiceless fricatives; 2) Indo-European voiced plosives were shifted into voiceless ones; 3) Indo-European voiced aspirated plosives were reflected either as voiced fricatives or as pure voiced plosives. Table 1 illustrates Grimm’s law.

Table 1. Grimm’s law.

| Indo-European | Germanic |

| 1 voiceless plosives p t k | Voiceless fricatives f þ h |

| Lat pater Lat trēs Gk kardia, Lat cordis | OE fæder (father) OE þrēō, Goth þreis (three) OE heorte, OHG herza (heart) |

| 2 voiced plosives b d g | Voiceless stops p t k |

| Rus болото Lat duo Lat gertu Gk egon | OE pōl (pool) Goth twai (two) OE cnēō (knee) OIcl ek (I) |

| 3 voiced aspirated plosives bh dh gh | Voiced non-aspirated stops b d g |

| Snsk nabhah, bhratar Snsk rudhiras, madhu Snsk songha Lat. hostis (enemy) | OE nifol (dark), brōðor OE rēād, medu (mead) OIcl syngva (sing) OE giest (guest) |

However, Grimm’s law did not cover all the instances, and later on, in the XIX century, they were explained by a Dutch linguist Karl Verner. According to Verner’s law, all the early Proto- Germanic voiceless fricatives [f, θ, x] which arose under Grimm’s law and also voiceless fricatives

[p, t, k, s] inherited from PIE, became voiced between vowels if the preceding vowel was unstressed; in the absence of these conditions they remained voiceless. The scheme below shows the corresponding sounds after the shift:

[f > b] Greek (IE) he p ta Goth (Germanic) si b un (seven)

[þ > đ > d] Greek (IE) pa t er OSc (Germanic) fa ð ir, OE fæ d er

[h > γ > g] Greek (IE) de k as Goth (Germanic) ti g us (ten, a dozen)

[s > z > r] Snsk (IE) aya s Goth (Germanic) ai z, OHG ē r (bronze)

Another feature of the Germanic languages is germination, or lengthened consonants. In the West Germanic languages the phoneme [j] following a single consonant was assimilated to this consonant which resulted in germination of the latter and loss of [j]. In this way long consonants appeared in the West Germanic subgroup as opposed to short consonants, e.g. Gothic saljan – OE sellan (give, sell); Gothic hlahian – OE hliehhan (laugh).

Gemination did not take place if the preceding vowel was long, e.g. Gothic dōmjan – OE dēman (judge); Gothic dailjan – OE dælan (divide). The only consonant which was never germinated was [r], e.g. Gothic arjan (plough) – OE erian; Gothic nasjan (save) – OE nerian.

3. One of the important processes in the reorganization of the Germanic morphological system was the change in the word structure. In Early Proto-Germanic the word consisted of three main components: the root, the stem suffix and the grammatical ending. The stem suffix was used to derive new words whereas the ending to mark grammatical forms. In Late Proto-Germanic stem suffixes lost their derivational force that resulted in simplification of word structure: the three morpheme structure was changed into a two morpheme structure. The former grammatical ending and the stem suffix formed a new ending, e.g. PG mak-ōj-an > OE mac-ian, Past Tense mac-ode (NE make, made).

Another feature that characterized the Germanic grammar was the division of verbs into two large groups: strong and weak. The main difference between them lay in the way of building the principal forms: the Present Tense, the Past Tense and Participle II. The strong verbs built them by means of root vowel interchange and certain grammatical endings; they employed Indo-European Ablaut with definite phonetic modifications. The weak verbs are an innovation in the Germanic languages. They built the Past Tense and Participle II with the help of a special dental suffix [ð].

Table 2

| Infinitive | Past Tense | Participle II | |

| OIcel call, called | Kalla | kallaða | kallað |

| OE make, made | Macian | macode | macod |

4. The Germanic languages have inherited and preserved many Indo-European features in vocabulary as well as at other levels. The words in the Germanic vocabulary may be divided into several groups according to their origin. The first layer is made up of roots shared by most Indo-European languages. They denote natural phenomena, basic activities of man, plants, animals, terms of kinship. Some pronouns and adjectives also belong here. Besides, the common Indo-European layer includes word-building affixes and grammatical inflections.

The second layer is made up of words which have parallels in the Germanic languages only. These words appeared in Proto-Germanic or in later history of separate languages from Germanic roots. Semantically, they also denote things and notions connected with the main spheres of life: home life, nature, sea. Like the Indo-European layer this one also includes word-building components. In the table below you can find examples of specifically Germanic words.

Table 3

| Gt | OIcel | OHG | OE | Sw | G | NE |

| hus land drigkan | hús land drekka | hûs lant trinkan | hūs land drincan | hus land dricka | Haus Land trinken | house land drink |

The Indo-European and the Germanic are native words. Besides, the Old Germanic languages had borrowings from other languages. A certain number of borrowings is supposed to have been borrowed before the migration of the West Germanic tribes to Britain. The borrowings reflect the contact of the tribesmen with Romans and the influence of the Roman civilization on their life; many of them belong to the semantic spheres of trade and warfare, e.g. L pondō, Gt pund, OIcel pund, OE pund, NE pound; L strata, OHG strâza, OS strata, OE stræt, NE street.

Table 4 below illustrates similarity of roots in some Germanic languages.

Table 4

| English | Frisian | Afrikaans | Dutch | German | Gothic | Icelandic | Faroese | Swedish | Norwegian (Bokmål) |

| Apple | Apel | Appel | Appel | Apfel | Aplus | Epli | Epl(i) | Äpple | Eple |

| Board | Board | Bord | Bord | Brett / Bord | Baúrd | Borð | Borð | Bord | Bord |

| Book | Boek | Boek | Boek | Buch | Bōka | Bók | Bók | Bok | Bok |

| Breast | Boarst | Bors | Borst | Brust | Brusts | Brjóst | Bróst | Bröst | Bryst |

| Brown | Brún | Bruin | Bruin | Braun | Bruns | Brúnn | Brúnur | Brun | Brun |

| Day | Dei | Dag | Dag | Tag | Dags | Dagur | Dagur | Dag | Dag |

| Dead | Dea | Dood | Dood | Tot | Dauþs | Dauður | Deyður | Död | Død |

| Finger | Finger | Vinger | Vinger | Finger | Figgrs | Fingur | Fingur | Finger | Finger |

| Give | Jaan | Gee | Geven | Geben | Giban | Gefa | Geva | Giva / Ge | Gi |

| Glass | Glês | Glas | Glas | Glas | Gler | Glas | Glas | Glass | |

| Gold | Goud | Goud | Goud | Gold | Gulþ | Gull | Gull | Guld/ Gull | Gull |

| Hand | Hân | Hand | Hand | Hand | Handus | Hönd | Hond | Hand | Hånd |

| Head | Holle | Hoof / Kop | Hoofd/ Kop | Haupt/ Kopf | Háubiþ | Höfuð | Høvd/ Høvur | Huvud | Hode |

| High | Heech | Hoog | Hoog | Hoch | Háuh | Hár | Høg/ur | Hög | Høy/høg |

| Home | Hiem | Heim / Tuis | Heim /Thuis | Heim | Háimōþ | Heim | Heim | Hem | Hjem/heim |

| Hook | Hoek | Haak | Haak | Haken | Krappa/ Krampa | Krókur | Krókur/ Ongul | Hake/ Krok | Hake/ Krok |

| House | Hûs | Huis | Huis | Haus | Hūs | Hús | Hús | Hus | Hus |

| Many | Mannich/Mennich | Menige | Menig | Manch | Manags | Margir | Mangir/ Nógvir | Många | Mange |

| Moon | Moanne | Maan | Maan | Mond | Mēna | Tungl/ Máni | Máni/ Tungl | Måne | Måne |

| Night | Nacht | Nag | Nacht | Nacht | Nótt | Nótt | Natt | Natt | Natt |

| No | Nee | Nee | Nee(n) | Nein (Nö, Nee) | Nē | Nei | Nei | Nej | Nei |

| Old | Âld | Oud | Oud, Gammel | Alt | Sineigs | Gamall (but: eldri, elstur) | Gamal (but: eldri, elstur) | Gammal (but: äldre, äldst) | Gammel (but: eldre, eldst) |

| One | Ien | Een | Een | Eins | Áins | Einn | Ein | En | En |

| Snow | Snie | Sneeu | Sneeuw | Schnee | Snáiws | Snjór | Kavi/ | Snö | Snø |

| Stone | Stien | Steen | Steen | Stein | Stáins | Steinn | Steinur | Sten | Stein |

| That | Dat | Dit, Daardie | Dat, Die | Das | Þata | Það | Tað | Det | Det |

| Two/ Twain | Twa | Twee | Twee | Zwei (Zwo) | Twái | Tveir/ Tvær/ Tvö | Tveir (/Tvá) | Två | To |

| Who | Wa | Wie | Wie | Wer | Ƕas (Hwas) | Hver | Hvør | Vem | Hvem |

Additional reading…

2014-09-04

2014-09-04 1111

1111